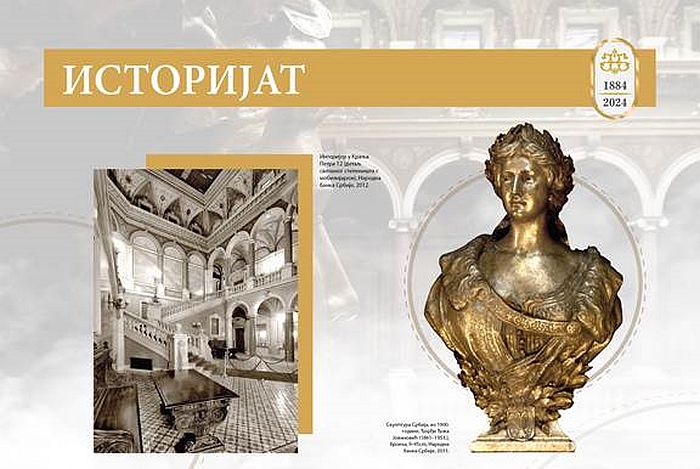

The NBS Head Office Building was built from 1888 – 1890, on the basis of blueprints designed by Konstantin Jovanovic (Vienna 1849 – Zurich 1923), son to distinguished artist Anastas Jovanovic...

After the Congress of Berlin in 1878 and the gaining of independence, Serbia entered a rather tumultuous period of internal and international developments. Once territorial liberation was achieved, Serbia embarked on the path of fast economic progress which was reflected, inter alia, in the construction of the railway, development of industry and mining, increased volume of trade and agricultural output. However, the absence of adequate legislation in finance hindered further progress. A law governing central bank operations was one of the essential regulations Serbia needed at the time.

The Law on the National Bank, ratified on 18 January 1883 (6 January according to the Julian calendar), was not only the basis for the founding of the Privileged National Bank of the Kingdom of Serbia as the institution competent for central banking and issue operations, but also a source of favourable loans to businesses and government as the cornerstone for strengthening financial and economic system in Serbia in general.

The founding assembly of the National Bank was held between 26 and 29 February 1884, and on 2 July 1884 (14 July according to the Julian calendar), in a rented space in the Kumanudi brothers’ house in Knez Mihailova Street, Belgrade, the Privileged National Bank opened its tellers to citizens and businesses. The construction of the bank’s own building in Dubrovačka Street, nowadays Kralja Petra Street, began in 1888 based on the project by the architect Konstantin A. Jovanović. The building welcomed the bank employees in 1890.

The National Bank had a wide governance apparatus composed of the governor, vice-governor, four councils (the Principal Council, Governing Council, Supervisory Council and Discount Council) and the Shareholders’ Assembly. The supervision of the entire Bank activity on behalf of the government and obtaining of the consent of state authorities for more efficient work of the institution were entrusted to a government commissioner.

In under two decades of the National Bank’s work and the overall development of lending activity in the country, the number of money bureaus rose to 92 or by 1,314% (11 banks, two credit bureaus, 31 savings banks and 48 assistance and savings cooperatives).

After the Balkan Wars, the Kingdom of Serbia was not expecting a new war. However, the assassination of the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne provided an excuse for Austro-Hungary to declare war on Serbia on 28 July 1914. The National Bank operated on Serbian soil in war conditions until 1 October 1915, when the royal government made the decision to begin a four-year exile through Niš, Skopje and Thessaloniki. Having spent several weeks in Thessaloniki, on 3 December 1915 the decision was made to move on towards Marseille. One of the National Bank’s first activities in Marseille was the exchange of the Serbian dinar for the French franc.

The creation of the Yugoslav state in 1918 gave rise to great expectations of economic development and the country’s progress. The Law on the National Bank was ratified on 26 January 1920, and already on 1 February the Bank took over the operations in the enlarged territory and started operating under the new name – the National Bank of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. The strengthening of the dinar, initiated in 1923, and its stabilisation since May 1925 normalised the banking circumstances. At end-1930, there were 642 banks operating in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia with a three-billion dinar principal. Having practically stabilised the dinar, the government set out to do the same in legal terms and in 1931 it passed the Law on the National Bank, backing the dinar with gold. Nevertheless, the crash of Austrian and German money bureaus, the US moratorium on the payment of German reparations and the UK abandoning the gold standard (21 September 1931) had a negative effect on the economy and balance of payments of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. Hence, the Government was forced to limit free trade in foreign currencies (October 1931), that is, to abandon the dinar convertibility. In order to save the stability of the domestic currency, Serbia switched to clearing payments. As of July 1938, deteriorating political circumstances, the threat of the expansion of the German Reich and changes to the national boundaries in Europe established by the Treaty of Versailles started affecting the previously satisfactory situation in the local foreign exchange market. To prevent the negative impact on the stability of the dinar, the National Bank, in agreement with the Ministry of Finance, took measures that entailed import controls, intervention in the domestic stock exchanges and the regulation of demand for free foreign currency in the domestic market.

To further strengthen government supervision and due to the increasing war psychosis, the Law on the National Bank was amended to allow for government borrowing. In a short period, from end-1940 until the capitulation, the quantity of money released into circulation was much greater than the amount of all the circulating money in the previous several years.

After the occupation of Yugoslavia and its partition in April 1941, the National Bank was forced to suspend its operation in the country and resume it in exile, together with the Government of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

On 29 May 1941, the German authorities issued the Decree on the Liquidation of the National Bank of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, but only a portion of the property which remained in the country could be liquidated. In the partitioned territory, the issuing role was taken over by the former banknote issuing banks of the occupying countries. The Serbian National Bank was established in the occupied Serbia, and it immediately started exchanging the Yugoslav dinar for the Serbian dinar.

Upon the end of the Second World War, the National Bank in exile ceased its operations. By the decree of royal regents, on 27 November 1945 the management of the National Bank in London were resolved of duty.

The new name – the National Bank of the Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia, was introduced on 15 January, and the Bank was nationalised on 25 September 1946. It thus became a full-fledged state bank. The period between the adoption of the Law on the Regulation and Operation of the Credit System (1945) and the adoption of the Regulation on Merging Credit Enterprises from the Government Sector (1946) covered the period of the nationalisation of banks in Yugoslavia, including the central bank. Finally, under the Government Decision of 20 March 1952, only one bank existed in the country – the National Bank of the FPRY, tasked with the additional duties of “social records and control”.

As the various forms of centralisation failed to yield the desired results, since mid-1950s the National Bank’s scope was narrowed, first with the establishment of specialised banks, such as the Yugoslav Investment Bank, Yugoslav Bank for Foreign Trade and Yugoslav Agricultural Bank. In the next phase of banking sector decentralisation (1961), of the tasks not customary for a central bank, the National Bank continued to engage in lending to the military industry, bodies and organisations of the federation, and in commodity reserves management. Another decentralisation measure included the removal of the national payment operations function from the National Bank’s competence in 1962 by setting up the Social Accounting Service as an independent body.

In March 1965, the new Law on the National Bank of Yugoslavia was adopted, drafted on the principles of banking system modernisation. It regulated the banking system which consisted of the National Bank of Yugoslavia, commercial banks and the Social Accounting Service. The National Bank was defined as the issuing bank of Yugoslavia, in charge of ensuring a single monetary, credit and foreign exchange system, and the conduct of monetary and credit policies based on its issuing, credit and international payments functions.

Constitutional amendments from 1971 established new monetary institutions besides the National Bank of Yugoslavia – the national banks of the republics and autonomous provinces. This was confirmed in the new Law on the National Bank of Yugoslavia (1972) and state and provincial laws on national banks (1973), whereby the country’s monetary system was (con)federalised.

A particularly absurd situation arose in 1983, when the National Bank of Yugoslavia became the guarantor of all foreign trade obligations of the country. A lasting consequence of this was that the (con)federalisation of competences enabled the national banks of the republics and provinces to undermine the National Bank of Yugoslavia. This culminated in the break-up of the joint Yugoslav state in 1991–1992.

In the years that followed, the Yugoslav territory was completely disintegrated. The dismemberment of the country was accompanied by military operations and the harshest sanctions imposed by the international community. All of this had a devastating effect on economic activity, and triggered hyperinflation in the monetary sphere. After several attempts to stabilise the dinar, the hyperinflation was stopped by the 1994 Monetary Stabilisation Programme.

Once the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia was declared in 1992, the National Bank was renamed into the issuing institution of the new state, comprising two republics – Serbia and Montenegro.

The Law from 1993 made the National Bank of Yugoslavia the legal successor to the rights and obligations of the National Bank of Yugoslavia for the territory of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and the rights and obligations previously held by the National Bank of Serbia, National Bank of Montenegro, National Bank of Vojvodina and the National Bank of Kosovo in the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.

With the Law on the National Bank of Serbia in 2003, the National Bank of Yugoslavia continued to operate as the National Bank of Serbia. Besides the Governor, two new bodies were established – the Monetary Policy Committee and the Council. After amendments to the Law in 2010, these two bodies became the Executive Board and the Council of the Governor.